Taming Your LLM Application

This is an article that sums up a talk I'm giving in Kaoshiung at the Taiwan Hackerhouse Meetup on Dec 9th. If you're interested in attending, you can sign up here

When building LLM applications, teams often jump straight to complex evaluations - using tools like RAGAS or another LLM as a judge. While these sophisticated approaches have their place, I've found that starting with simple, measurable metrics leads to more reliable systems that improve steadily over time.

Five levels of LLM Applications

I think there are five levels that teams seem to progress through as they build more reliable language model applications.

- Structured Outputs - Move from raw text to validated data structures

- Prioritizing Iteration - Using cheap metrics like recall/mrr to ensure you're nailing down the basics

- Fuzzing - Using synthetic data to systmetically test for edge cases

- Segmentation - Understanding the weak points of your model

- LLM Judges - Using LLM as a judge to evaluate subjective aspects

Let's explore each level in more detail and see how they fit into a progression. We'll use instructor in these examples since that's what I'm most familiar with, but the concepts can be applied to other tools as well.

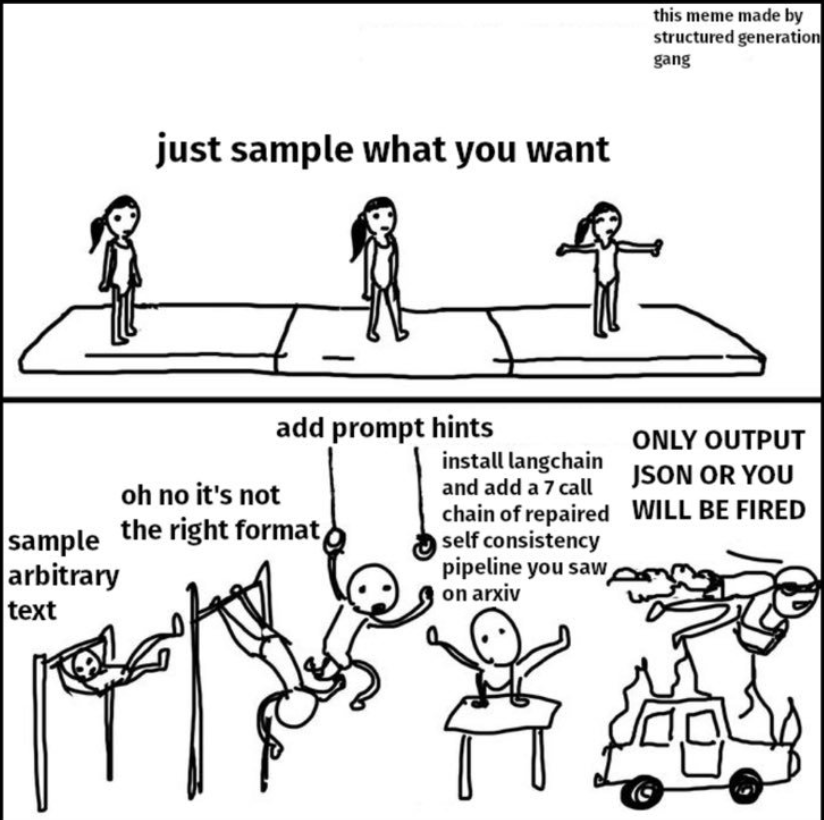

Structured Outputs

By using structured outputs, we don't need to deal with all the complex prompting tips that we've seen in the past. Instead, we can use a model that's either specifically trained to output valid JSON ( function calling ) or has some other way to ensure the output is valid.

If you're using local models, outlines is a great tool for this but if not, I highly suggest instructor for its wide coverage of LLM providers. Let's see it in action.

import instructor

from pydantic import BaseModel

from openai import OpenAI

# Define your desired output structure

class UserInfo(BaseModel):

name: str

age: int

# Patch the OpenAI client

client = instructor.from_openai(OpenAI())

# Extract structured data from natural language

user_info = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-3.5-turbo",

response_model=UserInfo,

messages=[{"role": "user", "content": "John Doe is 30 years old."}],

)

print(user_info.name)

#> John Doe

print(user_info.age)

#> 30

I'd like to point out a few things here

- We define a Pydantic model as the output - we don't need to handle the provider specific implementation details

- We prompt the model and provide the details for the output

- The final output is a validated python object

That's a lot of value already! We don't need to do any prompting to get this behaviour. Yes, our model might struggle with more complex structures but for most response types that have at most 1-2 layers of nesting, most modern models will do a great job.

This is great for 3 main reasons

- Wide Support : All major providers support structured outputs in some form. OpenAI has its structured outputs, Google's Gemini has its function calling while Anthropic has its tool use

- Reliability : By working with models and systems trained to output valid JSON, we can avoid the pitfalls of complex prompting. Better yet, by using a library like

instructor, we can experiment with different response models and see how they perform. Function Calling is much more consistent and reliable than JSON mode from experiments I've ran. - Metrics : Structured outputs give you your first real metrics - success rate. You'll frequently find that this is where Open Source models start to struggle a bit sometimes (Eg. Llama-3.1-70b) relative to closed source models that have infrastructure in place around them.

This makes it easy to integrate existing LLM calls into existing systems and workflows that we've built over time, log data in a structured format and remove a class of parsing errors that we'd otherwise have to deal with.

And all it took was just a simple response_model parameter and a .from_openai method.

Prioritizing Iteration

A LLM system is a complex beast with a lot of parts. Even a simple RAG chatbot has a few different components

- Retrieval : This retrieves the relevant documents from some database - most commonly a vector database

- Generation : This is how we generate a response from the documents

- Data Ingestion : How we're taking the raw data that we're ingesting and converting it into a format that we can use for retrieval

Instead of focusing on evaluating the generated response of the language model, starting with something like retrieval gives us a lot of bang for our buck.

It's important here to note that we're not saying that qualitative metrics don't matter (Eg. the style and tone of your final generation ), we're saying that you need to get the basic right and find areas that you can iterate fast.

Good metrics here are recall and mrr. If you don't have existing user queries, we can use synthetic data here to generate some queries and see how well we're doing ( I wrote a longer guide here on how to generate synthetic queries here with user intent in mind )

This doesn't have to be complicated, let's say given a following chunk

Taiwan is a lovely island which has Chinese as its official language. Their capital is Taipei and the most popular dishes here are beef noodle soup, bubble tea and fried chicken cutlets.

We can use instructor to generate potential queries simulating user intent

import instructor

from openai import OpenAI

from pydantic import BaseModel

from rich import print

client = instructor.from_openai(OpenAI())

class Response(BaseModel):

chain_of_thought: str

question: str

answer: str

chunk = """

Taiwan is a lovely island which has Chinese as its official language. Their capital is

Taipei and the most popular dishes here are beef noodle soup, bubble tea and fried

chicken cutlets.

"""

resp = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4o-mini",

response_model=Response,

messages=[

{

"role": "user",

"content": (

"Given the following chunk, generate a question that a user might ask "

f"which this chunk is uniquely suited to answer? \n\n {chunk}"

),

}

],

)

print(resp)

# > Response(chain_of_thought='...', question='What are some popular dishes in Taiwan?',

# answer='...')

We can quickly and cheaply generate a lot of these queries, manually review them to see which make sense and then use those to test our retrieval systems. Good metrics here to consider are recall and mrr.

Most importantly, we can use these queries to test different approaches to retrieval because we can just run the same queries on each of them and see which performs the best. If we were comparing say - BM25, Vector Search and Vector Search with a Re-Ranker step, we can now identify what the impact on recall, mrr and latency is.

Say we generate 100 queries and we find that we get the following results

| Method | Recall@5 | Recall@10 | Recall@15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BM25 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.82 |

| Vector Search | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.85 |

| Vector + Re-Ranker | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.79 |

We might conclude that for an initial prototype, shipping with BM25 is sufficient because we can match the performance of the other two methods with a simpler system - see how recall@15 for BM25 here matches recall@10 for Vector Search. This means that we can go from absolute recomendations that people give (eg. The BAAI/bge-m3 model is the best model! ) to specific decisions that are unique to our data.

But this doesn't just apply to retrieval itself, we can also use this to evaluate our choice of data ingestion method.

Say we were comparing two methods of ingesting data - one that ingest the description of an item and another that ingests the item's description, its price and categories it belongs to. We can use the same set of queries to see which performs the best ( since the underlying chunk doesn't change, just the representation that we're using to embed it ).

If we got the following reuslts

| Method | Recall@5 | Recall@10 | Recall@15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description Only | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.82 |

| Description + Price + Categories | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.90 |

It's pretty clear here that the second method is better because we get ~10% increase in recall across 5,10 and 15. We've identified an easy win here that takes a small amount of time to implement.

Most importantly, we can use these metrics to make a data driven decision about which approach to use. We're not going off some fuzzy "I think this might work better", we know that there's a quantitative objective difference. Since they're cheap and easy to calculate, you can run them multiple times without worrying about cost - locally while developing, in your CI/CD pipelines or even in production.

But these aren't just for simple question answering tasks. Good retrieval usually predicts good generation, especially as language models get better.

- Text-to-SQL: Look at whether you can retrieve the right tables and relevant code snippets

- Summarization: See if your model can generate the right citations

and more!

Synthetic Data

Now that you've got a pipeline running, you can use synthetic data to systematically probe your system's behavior. Language models are trained on the entire internet and that means that they understand variations and differences in the data that you might not have considered.

Let's say that we're using a LLM on the back to generate search filters in response to a user query and return relevant results to the user.

import instructor

from openai import OpenAI

from pydantic import BaseModel

from typing import Optional

from rich import print

client = instructor.from_openai(OpenAI())

class Filters(BaseModel):

city: Optional[str]

country: str

attraction_categories: list[str]

resp = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4o-mini",

response_model=Filters,

messages=[

{

"role": "system",

"content": "You are a helpful assistant that helps users generate search filters for a travel website to get recomendations on where to go. Make sure that you only include filters that are mentioned in the user's queries",

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "What's good in Taiwan to do? I generally like exploring temples, musuems and food",

},

],

)

print(resp)

# > Filters(city=None, country='Taiwan', attraction_categories=['temples', 'museums', 'food'])

We might want to make sure that our model is able to do the following

- In the event that there are no cities mentioned, then only a country should be returned

- In the event that the user mentions a city, then the city should be populated

We can generate variations of this query and see how well our model does.

from instructor import from_openai

from openai import OpenAI

from pydantic import BaseModel

import random

client = from_openai(OpenAI())

class RewrittenQuery(BaseModel):

query: str

for _ in range(3):

task = random.choice(["mention taipei", "don't metion any city"])

resp = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4o-mini",

response_model=RewrittenQuery,

messages=[

{

"role": "user",

"content": f"""Rewrite this query - What's good in Taiwan

to do? I generally like exploring temples,

musuems and food - {task}""",

},

],

)

print(resp)

# > What are some recommended activities in Taiwan? I enjoy exploring temples, museums, and local cuisine.

# > What are some great activities to do in Taipei, Taiwan? I particularly enjoy exploring temples, museums, and trying out local food.

# > What are some recommended activities in Taiwan for someone who enjoys exploring temples, museums, and food?

This is really useful when it comes to fuzzing your system for edge cases. By having a few different queries that you can test against, you can see how well your system performs for specific use cases.

More importantly, you can think of it as

- If the model always makes a mistake for a specific type of query, we can add it into the prompt itself with few-shot examples

- If few-shot examples don't work, then perhaps we can just add a step to reject any queries of type X

- Maybe this calls for a UI change too?

But more importantly, with these specific queries, we can see that

- We're moving away from just testing 3-5 different queries each time and relying on a vibe check

- We're able to systematically evaluate the impact of different configurations of retrieval method, generation and prompts in our language model ( among other factors )

- With synthetic data, we can generate a large variety of different queries that we can test against

Ideally we'd want to blend this with real user queries to get a good mix of both over time. We can to be re-generating these queries over time to ensure that we're still perfoming well + our synthetic queries are representative of the queries that users actually ask.

If users always ask stuff like "good food taiwan" but your synthetic queries are always long and overly complex like "I'm a solo traveller who likes to explore local food and culture in Taiwan, what are some great food places thT i can visit? I like ... " then you're not going to get a good sense of how well your system is doing.

Segmentation

The next step once you've started testing your LLM system is to understand its weak points. Specifically, you want to know which portions of your application aren't performing well.

This is where you need to do some segmentation and start breaking down your system into different components - This is an article on it's own but basically here's how to think about it

- Your application will be a combination of different components

- Each component will be able to do different things

- It's not going to score well on everything and so users will complain about it

- You need to weight the amount of effort required to improve each component + the amount of users that are actually affected by it

If you find that there's a huge problem with how your language model is handling dates for instance but only 2% of users are complaining about it, then perhaps spend your time elsewhere if there are other problems at bay.

Qualitative Evaluation

Language models can serve as powerful judges, particularly in two key areas: generating weak labels and evaluating subjective quality.

Weak Label Generation

LLMs excel at generating initial "weak" labels that humans can later verify. It's often much faster for humans to validate whether a classification is correct than to create labels from scratch.

For example, when building a reranker (as detailed in this instructor.com guide), we can use an LLM to generate initial relevance scores for query-document pairs.

Humans can then quickly verify these scores, dramatically speeding up the creation of high-quality training data. This approach works particularly well for tasks like intent classification, content categorization, and topic identification.

Style and Quality Assessment

Let me revise to keep the links while focusing on the key points:

LLMs make great judges in two key ways.

First, they're excellent at generating initial "weak" labels that humans can quickly verify - this is way faster (and significantly cheaper) than having humans label everything from scratch. For example, when building a reranker (as detailed in this instructor.com guide), we can use LLMs to generate initial relevance scores that human annotators can rapidly validate.

LLMs are also surprisingly good at judging subjective things like writing quality and conversational style, but you have to be smart about it. The key is making it an iterative process - start by having humans rate examples, use those to refine your prompts and evaluation criteria, then keep adjusting based on feedback. Vespa's deep dive by Jo offers a great walkthrough of this iterative improvement process.

The goal isn't perfect agreement out of the gate, but steady improvement through systematic refinement of how we ask LLMs to judge.

Conclusion

Building reliable LLM applications is a journey that starts with simple metrics and gradually adds sophistication. This shift allows teams to build systems that improve steadily based on data while keeping evaluation costs manageable.

Most importantly, this approach helps transform gut feelings into measurable metrics, enabling data-driven decisions about system improvements rather than relying on vague intuitions about what "feels better." The goal isn't to build a perfect system immediately, but to create one that can be measured, understood, and improved systematically over time.

There's a lot more that we can do here, but I hope that this gives you a good starting point for building more reliable LLM applications.